TEIGIN CASE: HIRASAWA SADAMICHI

JIADEP Note: One of the most notorious cases of wrongful arrest, a tenpera painter was arrested for the poisoning of 12 people at the Teikoku Bank in 1948. He denied any connection with the case and died in prison at the age of 95. Until recently, his supporters were still trying to clear his name. Exoneration after death is not alien to Japanese criminal justice, and one woman defendant in the Tokushima Radio Case, was found not guilty after her death. Needless to say, his adopted son recently died, and presently no one has standing to continue the case.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sadamichi_Hirasawa

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Teigin Incident: 70 years on, efforts continue to clear late artist's name in 1948 Tokyo mass murder

Paintings made over decades on death row displayed at gallery

- • Visitors to Gallery Ten in Tokyo's Taito Ward look at paintings drawn in prison by the late Sadamichi Hirasawa, who was convicted of mass murder in the Teigin Incident. The exhibition is being held to mark the 70th anniversary of the case. | KYODO

- •

- •

- • Feb 2, 2018

- •

Sadamichi Hirasawa was accused of killing 12 people with poison and stealing money from a Tokyo branch of Teikoku Ginko (Imperial Bank), which was known as Teigin, on Jan. 26, 1948.

After first confessing to the murders, Hirasawa backtracked at the start of his trial, maintaining his innocence until he died in prison in 1987, at age 95, after nearly 40 years of incarceration.

No justice minister ordered him hanged during his incarceration. Efforts to overturn the death sentence have continued, with his lawyers filing a 20th appeal for a retrial with the Tokyo High Court in 2015.

The paintings displayed at Gallery Ten in Taito Ward are among thousands of works Hirasawa created in prison, from the 1950s to the 1980s, with painting supplies provided by his family so he could continue his career.

One painting shows a red flower against a background of iron bars, cats, Mount Fuji and the face of his daughter. Letters including his works, addressed to his supporters, are also on display.

Before his arrest, Hirasawa was known for his landscape paintings depicting the spaciousness of his homeland of Hokkaido.

“But in prison, surrounded by concrete walls and iron bars, he had to depend on his imagination and memory to create his art,” said Eizo Yamagiwa, who leads a civil group working to raise public awareness of the Teigin case. “Mr. Hirasawa must have felt great sorrow over his discomfort.”

The Teigin Incident stunned the nation, which was reeling in the wake of World War II.

“We have to continue making efforts to prevent memories of the case from eroding, because injustice will continue unless his innocence is proved in a retrial,” said Yamagiwa, a longtime human rights activist.

The civil group also aims to restore Hirasawa’s reputation as a painter. His lawyers, for their part, are appealing to the high court to reopen the case.

They have submitted a written opinion by a psychologist who casts doubt over the credibility of Hirasawa’s confession during questioning and the observations of researchers who closely examined witness testimony, including that of survivors.

The psychologist, Sumio Hamada, a professor emeritus at Nara Women’s University, argues that interrogation records indicate Hirasawa apparently struggled to cast himself as the culprit of the crime because he apparently knew few of the details.

The researchers concluded that the memories of the witnesses were affected by the flood of reporting about the arrest of Hirasawa and other factors when they were required to identify him several months after the crime.

The 12 victims were killed by a man identifying himself as a public health official, who claimed dysentery had broken out in the neighborhood and urged them to take a “remedy” that turned out to be poison. The man then escaped with cash and checks.

Hirasawa was arrested seven months after the incident, allegedly based largely on flimsy evidence.

The lawyers also plan to conduct biological tests in cooperation with doctors to pin down what kind of poison was used to kill the victims, based on the persistent doubts over the court determination that it was potassium cyanide.

“We will depend on leading-edge science so we can identify the poison,” said Ryohei Watanabe, one of the lawyers, expressing hope that the findings could overturn the final judgment and lead to the reopening of the case.

The admission-free exhibition of Hirasawa’s in-prison drawings is being held through Feb. 4, open from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Artist, former death-row inmate Hirasawa's supporters try to put paintings in museums

December 5, 2015 (Mainichi Japan)

Japanese version

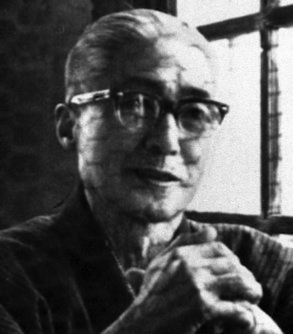

Eizo Yamagiwa, right, inspects "Chihei Seimei" (clear weather plain), a work said to be painted by Sadamichi Hirasawa before the poisoning incident, is seen in Saitama Prefecture, on Nov. 28, 2015. (Mainichi)

Former death-row inmate Sadamichi Hirasawa. (Mainichi)

Supporters of a former death-row inmate who left a large trove of paintings when he passed away in prison in 1987 are trying to have his works put in museums to pass them on to future generations.

- •

Hirasawa's supporters have contacted the city museum of art in his hometown of Otaru, Hokkaido, about accepting numerous works created before the poisoning. They are also looking for places to donate hundreds of pieces he made in prison.

Hirasawa was known as a leading figure in tempera painting in Japan. Before World War II he studied under Taikan Yokoyama, a master of Japanese-style painting. His subjects included the open spaces and nature of his native Hokkaido. His works were repeatedly accepted to the Teikoku Bijutsuin Tenrankai art exhibition, and he received permission to have his works displayed without having to go through the regular screening at the subsequent Monbusho Bijutsu Tenrankai art exhibition. Both exhibitions are predecessors of the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition, also known as Nitten.

After the poisoning case, however, Hirasawa's reputation as an artist fluctuated. While some of his works were kept at the prime minister's office, many others went missing. A man who became Hirasawa's adoptive child in 1981 to support a campaign for a retrial traveled around the country collecting Hirasawa's paintings. When the man died in 2013, many of these hundreds of works were left in the hands of Hirasawa's supporters.

A painting by Sadamichi Hirasawa created before the poisoning incident and that his supporters are trying to donate. (Mainichi)

Some of the works have started to show clear signs of deterioration, and Hirasawa's supporters, including 83-year-old movie director Eizo Yamagiwa, began searching for somewhere to donate the works to pass them on to future generations. This year, they suggested to the Otaru art museum that it accept numerous Hirasawa paintings from before the poisoning incident.

A representative for the museum says, "Hirasawa cultivated painters in Otaru, and otherwise endeavored to advance the growth of art. His works are very precious, and if certain conditions are met, we want to accept them."

Among the paintings are ones that were apparently seized temporarily by investigators to estimate Hirasawa's financial condition at the time of the poisoning incident.

A painting by Sadamichi Hirasawa created before the poisoning incident and that his supporters are trying to donate. (Mainichi)

Through donating the hundreds of Hirasawa illustrations from when he was in prison, his supporters also want to create an opportunity for people to think about the appropriateness of the death penalty system.

"Looking mainly at private museums, we want to find a place that will, as much as is possible, accept all the works," says a supporter.

In November this year, relatives of Hirasawa applied for the 20th time for a retrial. Nearly 70 years have passed since the poisoning incident, however, and many of Hirasawa's supporters are now elderly.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Death of inmate's adoptive son ends 'Teigin' retrial bid

Takehiko Hirasawa, shortly before he died. KYODO PHOTO

- BY KEIJI HIRANO

- Oct 16, 2013

Takehiko Hirasawa, 54, who sought a posthumous retrial for his adoptive father, Sadamichi Hirasawa, was recently found dead in a home in Suginami Ward, Tokyo.

Sadamichi Hirasawa was sentenced to hang for poisoning 12 people to death at a branch of Teikoku Ginko (Imperial Bank) in Tokyo on Jan. 26, 1948, in what became known as the “Teigin Incident.” He passed away in a prison hospital on May 10, 1987, at the age of 95, after maintaining his innocence for nearly 40 years.

The cause of the adoptive son’s death is not immediately known, but police have ruled out foul play.

His death will inevitably terminate the quest for a retrial unless the inmate’s surviving relatives take over, in accordance with legal stipulations over the right to seek a retrial.

Born the son of one of Sadamichi’s supporters, Takehiko became the prisoner’s adoptive son when he was still in college. He did so to take over the mission of reopening the case to exonerate the accused, an award-winning painter, as Sadamichi’s relatives were reluctant to seek a retrial due to social prejudice.

Since then, the adoptive son devoted his life to getting to the bottom of the crime.

“I could feel his determination to clear Mr. Hirasawa’s name, even to the extent of being adopted by him,” said Satoshi Yasuda, a longtime supporter of Sadamichi and Takehiko.

On the second anniversary of Sadamichi’s death, Takehiko filed the 19th petition for a retrial at the Tokyo High Court with the help of several lawyers volunteering their services.

Since then he had presented much new “evidence” to raise doubts over the final judgment. This included expert testimony rejecting the courts’ determination that the poison used in the crime was potassium cyanide.

Potassium cyanide would have acted immediately on the victims, but they died after a certain interval after being administered a drug by a man posing as a health official, suggesting another type of poison was used, according to the testimony.

Takehiko and the lawyers were also assembling position papers by psychologists.

By reviewing the investigation and court records, and by conducting experiments, the psychologists worked to determine if the testimony of eyewitnesses who identified Hirasawa as the murderer and if his confession during interrogation were credible.

The position papers were to be submitted to the court by the end of this year ahead of the verdict on the latest retrial petition.

It has also previously been claimed that someone linked to a secret wartime military unit known to have worked on chemical weapons was involved in the poisonings, given the murderer’s sophisticated modus operandi, knowledge of poisons and the substance’s delayed effect.

Takehiko also worked to recover lost paintings by Sadamichi and held several exhibitions.

He had detailed knowledge of the long history of the trial as he closely examined the trial records and made a study of various fields, including pharmacology, psychology and criminal procedure, according to Yasuda.

Apparently, however, given the uncertainty of knowing whether the case would be reopened and potential financial difficulty, Takehiko sometimes displayed signs of mental instability, particularly after his natural mother, who lived with him, died last December at 83, according to his supporters.

After her death, he wrote on the “Teigin Incident” website, “It was her wish and mine and my late father’s to mark in history that Sadamichi Hirasawa is innocent. I will continue this struggle for years to come.”

Contrary to what he wrote in December, however, he sometimes appeared to be losing heart in recent months, and, according to supporters, questioned if he could continue.

He is believed to have been dead for several weeks before his body was found in the Suginami house by supporters worried after not hearing from him.

“I didn’t expect the ‘Teigin Incident’ to end this way,” a supporter said while watching police enter and exit the house where Takehiko’s corpse was found.

Chief lawyer Keiichiro Ichinose said, “Many people have worked to exonerate Mr. Hirasawa, and their achievements will remain” even after the legal procedure to reopen the case is over.

The psychologists’ position papers will be eventually published so they can present their research to the public, according to the Tokyo-based lawyer.

Ichinose, who has been involved in the case for around 20 years, said, “I hope that some day it will be proved that Mr. Hirasawa suffered an injustice, as it should not remain uncorrected” despite Takehiko’s death.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Psychiatrist, 100, fights to clear late convict's name

Doctor sees judicial negligence parallels in Teigin Incident, rejection of Asahara insanity plea

By KEIJI HIRANO

Kyodo News

The Japan Times: Wednesday, May 10, 2006

A 100-year-old psychiatrist will lead the struggle to clear the name of Sadamichi Hirasawa, who spent decades on death row after being convicted of mass murder in a 1948 bank robbery known as the Teigin Incident.

"I believe Mr. Hirasawa is innocent, and it is deplorable that people have almost forgotten he was detained for more than 30 years with continual fear of execution," Haruo Akimoto said. "It is a terrible human rights violation by Japan's judicial system."

Hirasawa was arrested in August 1948 on suspicion of involvement in the fatal poisoning on Jan. 26 of that year of 12 people at a Teikoku Ginko bank branch in Tokyo. The poison was believed served to the victims by a man identifying himself as a public health official.

Hirasawa confessed to the slayings but later retracted his admission, claiming investigators forced him to make the statement. The Supreme Court upheld his death sentence based only on his initial confession.

Akimoto, a former professor at the University of Tokyo, will head a group campaigning for a retrial of Hirasawa's case on May 10, the 19th anniversary of his death from natural causes in a prison hospital at age 95.

After examining written expert opinions on Hirasawa's mental condition, in which psychiatrists said he had a tendency for delusions and was a habitual liar, Akimoto came to conclude he was innocent.

Akimoto said the psychiatrists had concluded these traits had multiplied at the time Hirasawa confessed due to his long detention.

"They should have concluded his mental condition was not usual and his confession was unreliable, because his tendency (to lie) intensified at that time," Akimoto said.

"I expect more and more people think that an innocent man was falsely charged and ended up dying in prison, because 33 different justice ministers refused to sign the execution order before his natural death," he said.

Such judicial negligence and lack of concern for human rights continues today, Akimoto said.

His concern about the judicial system has grown since the Tokyo High Court rejected an appeal by Aum Shinrikyo founder Shoko Asahara, who faces the gallows for masterminding the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system and other crimes.

The high court concluded in March that Asahara, whose real name is Chizuo Matsumoto, is mentally competent, rejecting the conclusion of examinations by six prominent psychiatrists, including Akimoto, that the guru is not competent.

Akimoto interviewed Asahara in February at the Tokyo Detention House and concluded the cult leader, who did not respond during the exam, is a "living corpse."

"I do not mean to defend Asahara, but to advocate the truth that he is mentally incompetent," he said. "The other five doctors reached the same conclusion, but the court adopted a false exam result by a court-appointed psychiatrist and ignored ours. This may damage public trust in psychiatric exams.

"A court cannot fulfill its duty -- protection of human rights -- if it ignores the truth," he said.

Hirasawa was another victim of injustice, Akimoto said.

"While I have had many experiences during my 100 years, my encounters with the Teigin Incident and Asahara are among the unforgettable ones," he said.

Takehiko Hirasawa, 47, Hirasawa's adopted son, said, "Dr. Akimoto has worked earnestly to prove the innocence of my deceased father, and I expect him to lead our support group so the memory of the Teigin Incident will not fade away."

The son was adopted by the Hirasawa family when he was 22 in order to support the retrial campaign that was headed by his real father, Tetsuro Morikawa, a well-known writer.

The campaigners filed the 19th petition for a retrial with the Tokyo High Court on May 10, 1989, the second anniversary of Hirasawa's death, and submitted what they claim was new evidence to prove his innocence.

The items include a memorandum by an investigator that indicates the investigation team believed someone from a secret unit within the old Imperial Japanese Army must have been involved in the murder due to the rareness of the poison used.

The high court has been examining the documents submitted by the campaigners and lawyers since 2004.

"It is insufficient if we focus only on persuading the court to reopen the case. We need to raise public awareness about the Teigin Incident to realize a retrial a half a century after the initial trial ended," Akimoto said.

The Japan Times: Wednesday, May 10, 2006

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~